The city's role in cultural development

In order for a city to plan its cultural development, many argue that efforts must be aimed at attracting those educated and creative individuals who can bring culture to their city.[1] The difficulty here is trying to create places that will attract these individuals, while at the same time minimizing the gentrification effects these measures can have on the existing population. Austin has been very successful when it comes to attracting a large population of educated people since the construction of the University of Texas. This, coupled with the prevalence of long-standing communities that surround the center of Austin, has led to a culturally rich city that has maintained much of its original uniqueness.

What’s interesting about Austin’s beginnings is that it was not chosen as the capital of The Republic of Texas because of its strategic location or abundance of resources. It was chosen because the president at the time thought the land was beautiful and wanted to have his capitol office there. This means Austin did not have any already-established industries or sources of economic development when the city was founded. For many years, the only development in the city was that connected to the state capitol and the University of Texas.[1]

|

Despite Austin not being founded for typical reasons, the city’s center adopted traditional planning schemes very early on (see “Austin's Founding”). Quickly, though, the communities that surrounded Austin began to grow rapidly and organically with little oversight from the city’s government. The early 20th century brought even more organic growth as many Austinites refused to accept planning policies because they felt any type of building regulation or slow growth measure would hurt the development of the city. People started to warm up to the idea of stricter city planning, however, when large buildings began to block out the once iconic views of Austin, such as the state capitol dome. Figure 1 shows how much of Austin's downtown skyline was being dominated by these large buildings.

|

Even with this new push for formal planning towards the end of the 20th century, many communities refused to adopt what the city had to offer. South Congress, for example, wanted to continue growing in its organic ways. Its residents did not want transportation or other improvements that would encourage an influx of outside investors and developers.[2] Largely, Austin residents wanted to keep Austin, Austin.

|

One type of development that benefited both the city’s economy and its culture was the construction of new museums, public art pieces, and parks. These cultural investments by the city started in the 1980s, making Austin a very attractive city to large tech companies (such as Dell) that were looking for places to base their headquarters.[1]

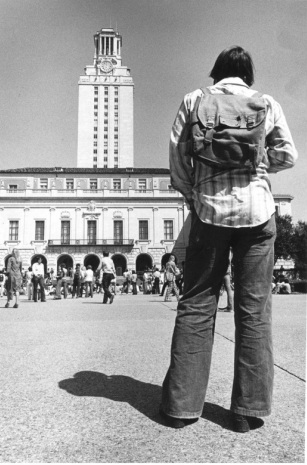

The city also invested a sizable amount of money in the University of Texas at Austin (see Figure 2), as well as in local aspiring musicians through loan programs and the creation of the city’s music commission in the late 1990s.[1] The growth of both these two scenes built off one another and helped Austin become “The Live Music Capital of the World.” Figure 3 depicts an example of a band which is able to perform because of the city's support of museums and local musicians. Today, the city supports 120 live music venues and 1,000 resident musicians.[3] Through specific actions taken by the city in conjunction with Austin’s history, the City of Austin has become a cultural hub for the country. The planners who pushed for cultural development were successful because they created an environment that was attractive to those educated young individuals who brought and continue to progress Austin’s culture. A lot of this success can also be attributed to the large student population who supported these cultural outlets as well as the city’s residents who slowed development and approved improvements to the city’s cultural infrastructure. |

- Grodach, Carl. "Before And After The Creative City: The Politics Of Urban Cultural Policy In Austin, Texas." Journal of Urban Affairs 34.1 (2012): 81-97. Web. 20 Aug. 2014.

- Patoski, Joe N. "National Trust for Historic Preservation." Preservationnation.org. Preservation Magazine, July-Aug. 2010. Web. 20 Aug. 2014. <http://www.preservationnation.org/magazine/2010/july-august/austin-tx.html>.

- "Austin Cultural & Recreational Activities." Texas Executive Education. University of Texas at Austin McCombs School of Business, n.d. Web. 20 Aug. 2014. <http://www.mccombs.utexas.edu/execed/participant-resources/culture-and-recreation>.

- Douglass, Neal. Street Scene -- Downtown Austin, Photograph, October 5, 1949; digital image, (http://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth62974/ : accessed September 02, 2014), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, http://texashistory.unt.edu; crediting Austin History Center, Austin Public Library, Austin, Texas.

- [Saxophonist, Bassist, and Singer Performing], Photograph, 1997; digital images, (http://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth304228/ : accessed September 02, 2014), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, http://texashistory.unt.edu; crediting Mexic-Arte Museum, Austin, Texas.