COLONIZATION: AUSTIN TAKES SHAPE

Figure 1: Stephen F. Austin, [M1]

Figure 1: Stephen F. Austin, [M1]

Stephen F. Austin and the Colony Plan

After word of his father’s passing, Stephen F. Austin carried on with his father’s Spanish approved and Mexican honored colonization venture in a Texas, then under a newly independent Mexico. Baron De Bastrop, as he once assisted his father, again lends his advice and acted as an intermediary between Stephen Austin and the Mexican government, contributing to the ultimate success of the colony. In fact, Steven F. Austin was such a successful empresario while still under Augustín de Iturbide’s reign, he lobbied in Mexico City to approve the Imperial Colonization Law of 1823, where in the end, he was also the only one to benefit from its provisions. This law was integral in incentivizing both the empresario and the settlers. For settlers, it allowed for one league for grazing (442.4 acres) and one labor (177.1 acres) for farming, a six-year tax exemption, naturalization of citizenship in Mexico after three years, and allowed the empresario to collect fees from the colonists in addition to being given free land. [1]

Growth of Austin’s Venture in Texas under Mexico

In 1823, Austin selects rich bottomland areas on the Colorado and Brazos rivers for his colony and provided a highly desirable opportunity for 300 families. Stephen Austin, by observing settlers moving into wilderness land with little supervision, opted for a plan featuring surveying done in advance of settlement. Such surveying practices were proposed to avoid litigation, strife, and boundary problems. Austin established these surveying standards and practice that were later adopted into the Republic of Texas. For example, surveyors were hired to construct maps on which tracts of land and surveys in specific locations could be consulted by colonists who would then receive their government issued titles issued by commissioners Baron de Bastrop in 1824 and Gaspar Flores in 1827-28. The end of Iturbide’s reign was marked in 1823 with the formation of a federal republic and in 1824 congress enacted its National Colonization Law, passing most land use powers to the states. At this time the former provinces of Coahuila and Texas were united to form a new state of the federation. Growth and augmenting territory by increased population was further spurred on by the State Colonization Law of Coahuila y Texas in 1825, which provided favorable terms governing immigration and settlement. [1]

In 1827, a decree issued the designation, responsibilities and detailed duties of land commissioners for the state as appointed by the governor by allowing issued titles and the authority of commissioners to take a strategic part in the laying out of new towns, supervision of surveys and maintenance of land records among other duties. For instance, “commissioners would take the oath of allegiance from new settlers, appoint surveyors, select sites and mark the streets for the new towns.”[1] Because the state of Coahuila and Texas lacked a centralized land office responsible for administering its public lands the governor was given the authority to appoint these commissioners.

Families of Austin’s Colonies & Their Success

According to the History of Texas Public Lands report from the Texas General Land Office, Stephen F. Austin issued close to 2000 titles from 1823-1828, each representing a colonial family and collectively millions of acres of Texas land. What is interesting and aside from his political prowess, what may have likely contributed to the colonies success and growth is Austin’s colonization plan was the selectiveness of the families he would allow. Generally, the colonists whom Austin personally registered were educated, certifiably of “Christian morality and good habits,” and lived on farms or cotton and sugarcane plantations of which they established as opposed to towns. These were not preferences, but for the most part characteristics of any settler who hoped to live in one of Austin’s colonies. It’s interesting to note that, the Austin colony was the first legal settlement of North American families and was also dominantly Anglo-American of British decent.

“The settlement of Austin's colony from 1821 to 1836 has been called the most successful colonization movement in American history. Many of the historical events of Southeast Texas owe their origin to this colony.” [2] During this time, war was underway during the Texas revolution that spanned from 1835-1836, at which Texas was declared separate from Coahuila. [3]

From Austin, Republic of Texas to Austin, Texas, U.S.A.

The state capital of Texas, USA was once the national capital of the Republic of Texas. And further, it is suffice to say, the capital resting on Austin was not to become assuredly permanent, as commissions of the Republic chose a few other temporary sites before joining the Union and it wasn’t until 1870 when Austin, Texas was established in the location known today. [2]

After word of his father’s passing, Stephen F. Austin carried on with his father’s Spanish approved and Mexican honored colonization venture in a Texas, then under a newly independent Mexico. Baron De Bastrop, as he once assisted his father, again lends his advice and acted as an intermediary between Stephen Austin and the Mexican government, contributing to the ultimate success of the colony. In fact, Steven F. Austin was such a successful empresario while still under Augustín de Iturbide’s reign, he lobbied in Mexico City to approve the Imperial Colonization Law of 1823, where in the end, he was also the only one to benefit from its provisions. This law was integral in incentivizing both the empresario and the settlers. For settlers, it allowed for one league for grazing (442.4 acres) and one labor (177.1 acres) for farming, a six-year tax exemption, naturalization of citizenship in Mexico after three years, and allowed the empresario to collect fees from the colonists in addition to being given free land. [1]

Growth of Austin’s Venture in Texas under Mexico

In 1823, Austin selects rich bottomland areas on the Colorado and Brazos rivers for his colony and provided a highly desirable opportunity for 300 families. Stephen Austin, by observing settlers moving into wilderness land with little supervision, opted for a plan featuring surveying done in advance of settlement. Such surveying practices were proposed to avoid litigation, strife, and boundary problems. Austin established these surveying standards and practice that were later adopted into the Republic of Texas. For example, surveyors were hired to construct maps on which tracts of land and surveys in specific locations could be consulted by colonists who would then receive their government issued titles issued by commissioners Baron de Bastrop in 1824 and Gaspar Flores in 1827-28. The end of Iturbide’s reign was marked in 1823 with the formation of a federal republic and in 1824 congress enacted its National Colonization Law, passing most land use powers to the states. At this time the former provinces of Coahuila and Texas were united to form a new state of the federation. Growth and augmenting territory by increased population was further spurred on by the State Colonization Law of Coahuila y Texas in 1825, which provided favorable terms governing immigration and settlement. [1]

In 1827, a decree issued the designation, responsibilities and detailed duties of land commissioners for the state as appointed by the governor by allowing issued titles and the authority of commissioners to take a strategic part in the laying out of new towns, supervision of surveys and maintenance of land records among other duties. For instance, “commissioners would take the oath of allegiance from new settlers, appoint surveyors, select sites and mark the streets for the new towns.”[1] Because the state of Coahuila and Texas lacked a centralized land office responsible for administering its public lands the governor was given the authority to appoint these commissioners.

Families of Austin’s Colonies & Their Success

According to the History of Texas Public Lands report from the Texas General Land Office, Stephen F. Austin issued close to 2000 titles from 1823-1828, each representing a colonial family and collectively millions of acres of Texas land. What is interesting and aside from his political prowess, what may have likely contributed to the colonies success and growth is Austin’s colonization plan was the selectiveness of the families he would allow. Generally, the colonists whom Austin personally registered were educated, certifiably of “Christian morality and good habits,” and lived on farms or cotton and sugarcane plantations of which they established as opposed to towns. These were not preferences, but for the most part characteristics of any settler who hoped to live in one of Austin’s colonies. It’s interesting to note that, the Austin colony was the first legal settlement of North American families and was also dominantly Anglo-American of British decent.

“The settlement of Austin's colony from 1821 to 1836 has been called the most successful colonization movement in American history. Many of the historical events of Southeast Texas owe their origin to this colony.” [2] During this time, war was underway during the Texas revolution that spanned from 1835-1836, at which Texas was declared separate from Coahuila. [3]

From Austin, Republic of Texas to Austin, Texas, U.S.A.

The state capital of Texas, USA was once the national capital of the Republic of Texas. And further, it is suffice to say, the capital resting on Austin was not to become assuredly permanent, as commissions of the Republic chose a few other temporary sites before joining the Union and it wasn’t until 1870 when Austin, Texas was established in the location known today. [2]

Location, location, location

In March of 1836 the Texas Declaration of Independence, urgently produced over one night officially established Texas as separate from Coahuila. Now under the Republic of Texas, an item on the agenda of high priority to Congress is to locate the nation’s capital. Early under the republic, under the second president, Sam Houston, Congress moved the capital, or as it was then called “The Seat of Government”, in 1837 to a newly formed town, not coincidentally given the name Houston, with the intent on producing a permanent location for the national capital by 1840. [3]

But it is 1839 when three different Republic of Texas commissions collectively determine and justify Austin’s colonies, which were among the rich, bottomlands with small, healthy farms and plantations along the river’s and creeks, to be the site that will become Austin. Under the third President, Mirabeau B. Lamar, the specific site for the capital, “to be named Austin, would rest somewhere along or between the Colorado and Trinity Rivers above the Upper San Antonio Road and below the falls.” The site fell on Stephen F. Austin’s second colony that contained a town named Waterloo, nominally established in 1838 by General Edward Burleson. Some of the many factors influencing the selection of the site include the following: Waterloo, still a frontier town, was not heavily inhabited, it had the city laid out but not developed, it was in a strategic location to bulwark against the Indians, it was an approximate geographic center of the present state and was believed to be at an advantageous proximity to Santa Fe. [4]

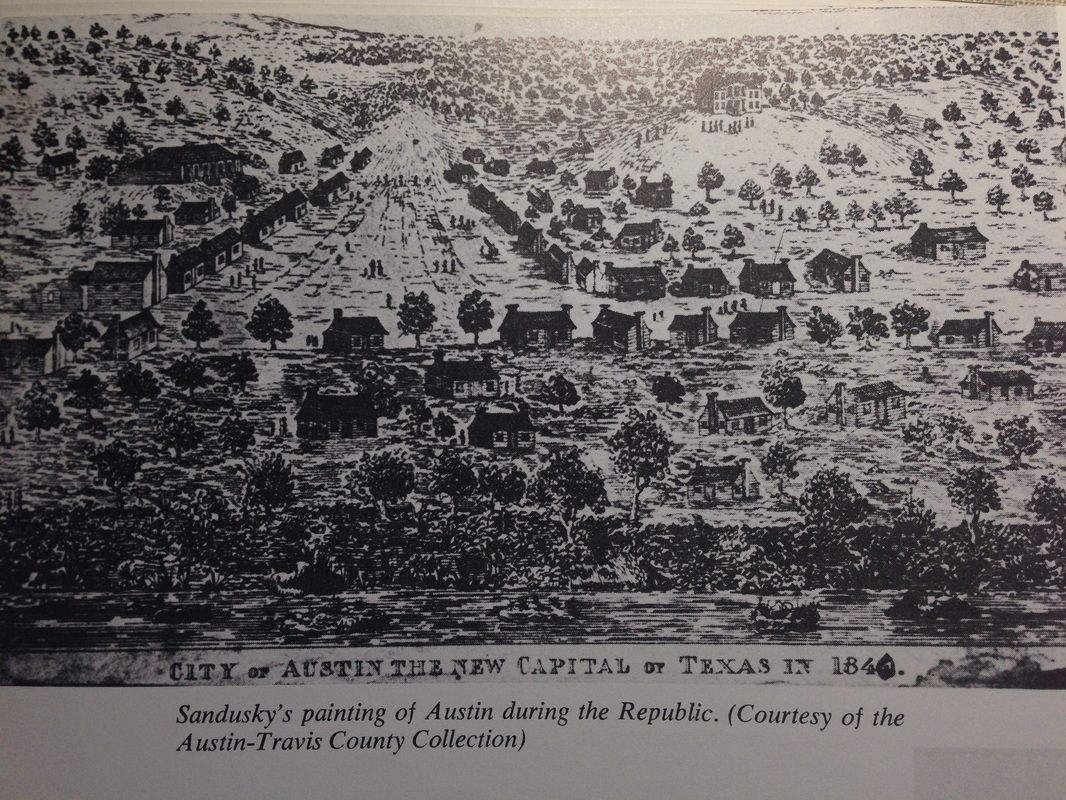

Interestingly, other geographic and environmental considerations that were noted was the perceived “healthfulness” and visible beauty, as it was on hilly, elevated ground near the Colorado river in which fertile woodlands, oak and cedar laden mountains and limestone formations were within viewing distance. [4]

More so, The Report of the Commissioners Named to Select a Permanent Capital for the Republic of Texas, dated April 13, 1839 even states “… a truly National City at no other point within the limits assigned them be reared up, not that other sections of the Country are not equally fertile, but that no other combined so many and such varied advantages and beauties as the one in question. The imagination of even the romantic will not be disappointed on viewing the Valley of the Colorado and the fertile and gracefully undulating woodlands and luxuriant Prairies… and the citizen’s bosom must swell with honest pride when standing in the Portico of the Capitol of his Country he looks abroad…” it inspiringly reads on to speak of the fire of patriotism, Nationality and romantic landscape from the aura of the site. [4]

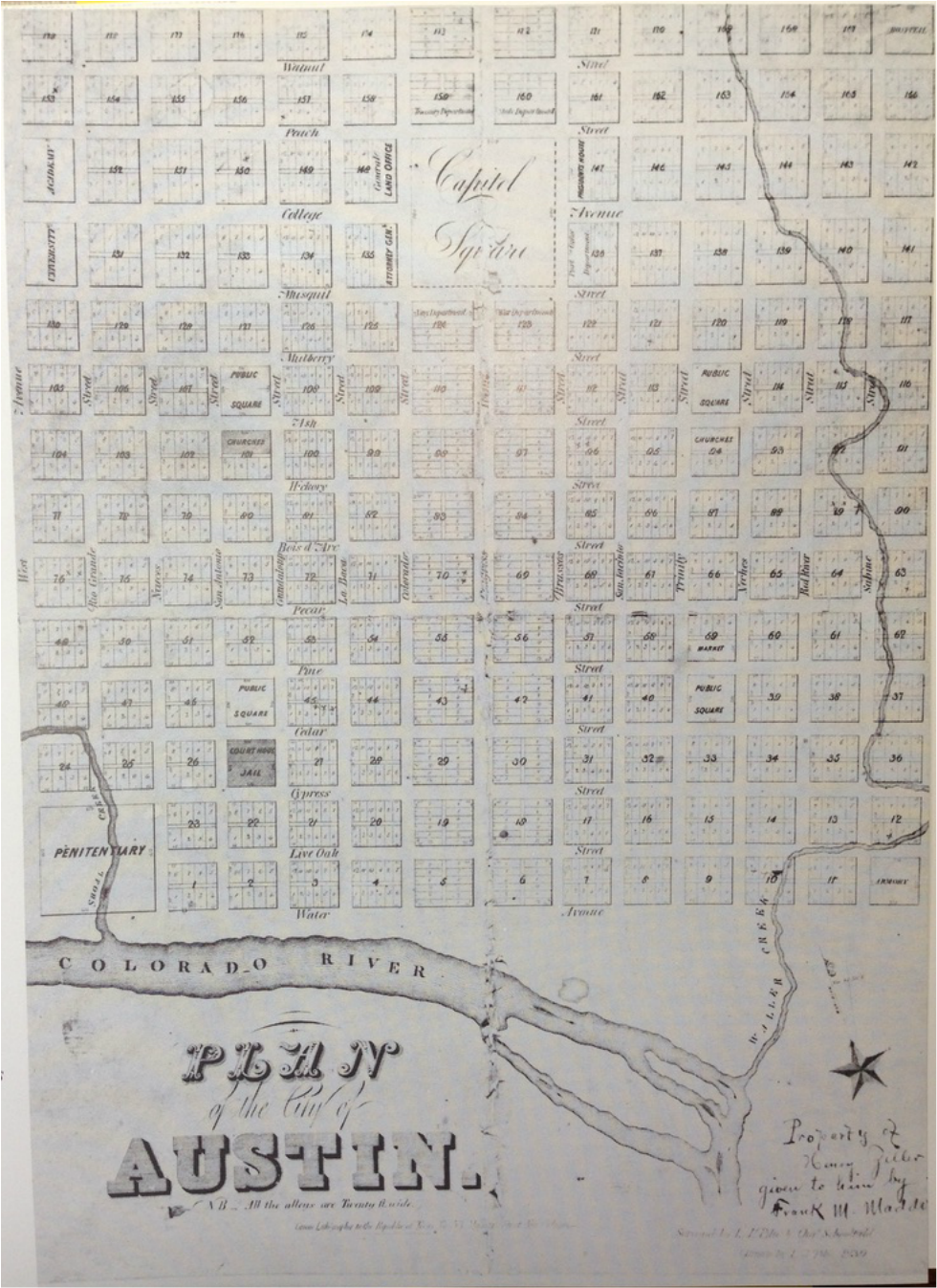

Surely, the climate, geology and ultimately the general environment significantly influenced the selection of Waterloo to become Austin. The design and plan of the city was commissioned to L.J. Pilie in 1839, as shown in figure 3 below, and remarkably much of the original plan is respected in the city today. The plan was influenced by the city plan of Washington D.C. in the manner by which prominence and emphasis of principal buildings was designed for on the given terrain. The initial 1839 plan contains a symmetrical, fourteen by fourteen block, grid structure which is superimposed over the hills of Austin assuming a character of balance that is further accentuated by the central axis of Congress avenue running North to South and its intersecting perpendicular axis (College Avenue then, 12th Street now) converging on the elevated, capital building grounds. It is interesting to note the North-south streets were named for rivers of Texas and cross streets took on names of Texas trees, both with the exception of the boundaries. [4]

In March of 1836 the Texas Declaration of Independence, urgently produced over one night officially established Texas as separate from Coahuila. Now under the Republic of Texas, an item on the agenda of high priority to Congress is to locate the nation’s capital. Early under the republic, under the second president, Sam Houston, Congress moved the capital, or as it was then called “The Seat of Government”, in 1837 to a newly formed town, not coincidentally given the name Houston, with the intent on producing a permanent location for the national capital by 1840. [3]

But it is 1839 when three different Republic of Texas commissions collectively determine and justify Austin’s colonies, which were among the rich, bottomlands with small, healthy farms and plantations along the river’s and creeks, to be the site that will become Austin. Under the third President, Mirabeau B. Lamar, the specific site for the capital, “to be named Austin, would rest somewhere along or between the Colorado and Trinity Rivers above the Upper San Antonio Road and below the falls.” The site fell on Stephen F. Austin’s second colony that contained a town named Waterloo, nominally established in 1838 by General Edward Burleson. Some of the many factors influencing the selection of the site include the following: Waterloo, still a frontier town, was not heavily inhabited, it had the city laid out but not developed, it was in a strategic location to bulwark against the Indians, it was an approximate geographic center of the present state and was believed to be at an advantageous proximity to Santa Fe. [4]

Interestingly, other geographic and environmental considerations that were noted was the perceived “healthfulness” and visible beauty, as it was on hilly, elevated ground near the Colorado river in which fertile woodlands, oak and cedar laden mountains and limestone formations were within viewing distance. [4]

More so, The Report of the Commissioners Named to Select a Permanent Capital for the Republic of Texas, dated April 13, 1839 even states “… a truly National City at no other point within the limits assigned them be reared up, not that other sections of the Country are not equally fertile, but that no other combined so many and such varied advantages and beauties as the one in question. The imagination of even the romantic will not be disappointed on viewing the Valley of the Colorado and the fertile and gracefully undulating woodlands and luxuriant Prairies… and the citizen’s bosom must swell with honest pride when standing in the Portico of the Capitol of his Country he looks abroad…” it inspiringly reads on to speak of the fire of patriotism, Nationality and romantic landscape from the aura of the site. [4]

Surely, the climate, geology and ultimately the general environment significantly influenced the selection of Waterloo to become Austin. The design and plan of the city was commissioned to L.J. Pilie in 1839, as shown in figure 3 below, and remarkably much of the original plan is respected in the city today. The plan was influenced by the city plan of Washington D.C. in the manner by which prominence and emphasis of principal buildings was designed for on the given terrain. The initial 1839 plan contains a symmetrical, fourteen by fourteen block, grid structure which is superimposed over the hills of Austin assuming a character of balance that is further accentuated by the central axis of Congress avenue running North to South and its intersecting perpendicular axis (College Avenue then, 12th Street now) converging on the elevated, capital building grounds. It is interesting to note the North-south streets were named for rivers of Texas and cross streets took on names of Texas trees, both with the exception of the boundaries. [4]

SOURCES:

[1] History of Texas Public Lands

http://www.glo.texas.gov/what-we-do/history-and-archives/_documents/history-of-texas-public-lands.pdf

[2] Austin's Colony, Texas A&M Class Website

http://www.tamu.edu/faculty/ccbn/dewitt/adp/history/hispanic_period/tenoxtitlan/austins_colony.html

[3] The Handbook of Texas Online: Texas State Historic Association (TSHA)

http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/fau12

[4] Roxanne Kutter Williamson, Austin, Texas: An American Architectural History. San Antonio: Trinity University Press,1973.

MEDIA:

[M1] Stephen F. Austin portrait

http://www.texasranger.org/halloffame/Austin_Stephen.html

[1] History of Texas Public Lands

http://www.glo.texas.gov/what-we-do/history-and-archives/_documents/history-of-texas-public-lands.pdf

[2] Austin's Colony, Texas A&M Class Website

http://www.tamu.edu/faculty/ccbn/dewitt/adp/history/hispanic_period/tenoxtitlan/austins_colony.html

[3] The Handbook of Texas Online: Texas State Historic Association (TSHA)

http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/fau12

[4] Roxanne Kutter Williamson, Austin, Texas: An American Architectural History. San Antonio: Trinity University Press,1973.

MEDIA:

[M1] Stephen F. Austin portrait

http://www.texasranger.org/halloffame/Austin_Stephen.html